M.V. EMPIRE WINDRUSH

DESTROYED BY FIRE

28th MARCH 1954

1,276 PASSENGERS SAVED - 4 CREW MEMBERS DIED

MEMORIES & OFFICIAL REPORT

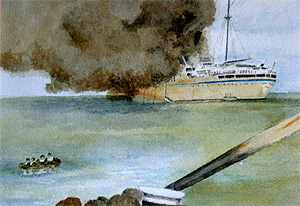

Empire Windrush on Fire

After two and a half years in the Canal Zone, I returned to England on the Empire Windrush – as far as Cape Caxine in Algeria anyway!! I completed my journey by Lifeboat, an Algerian ship and, after an overnight stay in an Algerian Army Camp, by the Aircraft Carrier H.M.S. Triumph to Gibraltar and finally by plane to Blackbush Airport.

Here are a few photographs, one of which I took on the Boat Deck before climbing into the lifeboat. The others were taken in the lifeboat under poor conditions – I was supposed to be rowing and it was quite difficult to take photos at the same time!! Unfortunately some of the negatives were spoilt by focussing or seawater etc.

The photo of the painting is something I did some time later in colour as the

photos were in black and white.

- As Remembered By George Nutt ex: RAF No. 1 GCI El Firdan

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Ex. WRAF, SACW Betty Palfrey has spoken quite frequently about events experienced

while she was serving in RAF Station, Abyad. Little did she know that when she

set sail on the Empire Windrush en route to Port Said and her posting in Egypt

in 1952, that she would sail on the same ship to return to UK in 1954. Although

her outbound trip in 1952 was uneventful, the same could not be said for the

return voyage in 1954. Betty spoke of her friendship with Elsie Hancock whom

she served with in the Canal Zone between 1952 and 1954. They were part of a

billet of eight working in administration for the equipment stores and shared

good times and bad times together.

The two were reunited after Betty saw an article in a national magazine and

they wrote to each other for many years before meeting up again after about

50 years. Betty said, ‘It was lovely to talk about old times – as

we all do whenever we meet fellow CZ veterans’. They vowed to remain in

contact.

Fire aboard Empire Windrush

Betty has vivid memories of the tragic voyage of Empire Windrush that she boarded

at Port Said. She served in Egypt for two years and in 1954 she embarked on

Empire Windrush in Port Said where it docked on its route from Yokohama to UK.

It had left Japan four weeks earlier carrying passengers and wounded soldiers

from the Korean War and also some married families.

The ship was plagued with engine breakdowns and other defects and it had reported engine trouble in the Suez Canal. Then at 0600 hours, just off Algiers, the passengers were awakened with the order to abandon ship. A fire had started when the ship’s engine exploded killing four engineer crewmembers. Flames and smoke was pouring from the engine room and paint was falling off the funnels in great flakes.

Empire Windrush ablaze

Fire ripped through the ship and because of a lack of electrical power the fire could not be fought and it also prevented some lifeboats from being launched. But the crew lowered the serviceable lifeboats and women and children were put first. Sadly these lifeboats were unable to accommodate all the survivors whom were mostly clad in their night-clothes. It was a miraculous disciplined rescue. There were no casualties and all 1 276 passengers were saved and taken by rescue vessels to Algiers. MV Mentor, MV Socotra, SS Hemsefjell and SS Taigete gave assistance in response to Mayday distress calls and a Shackleton from 224 Squadron, RAF also assisted. HMS Saintes attempted to tow the burnt out hulk of Empire Windrush to Gibraltar but in worsening weather the vessel sank before first light the following morning. The survivors were taken by aircraft carrier HMS Triumph to Gibraltar from where some were flown home.

One of the lifeboats

Betty and her colleagues carried out fire and emergency drills

on a daily basis, so it was nothing new when they heard the alarms sounding

in the night. They carried out the normal procedures and did not panic even

when they were told that this was the real thing. Betty said that there was

no panic because everyone knew what he or she had to do. They collected their

personal belongings and eight of them were picked up by one of the rescue vessels

and eventually arrived at Liverpool. It was an experience that none of us would

have liked to go through.

HISTORY OF THE WINDRUSH

The Monte Rosa, was delivered to Hamburg Süd in 1931, who operated her as a cruise ship, traveling to Norway, the United Kingdom and the Mediterranean. After the Nazi regime came to power in Germany in 1933, she was operated as part of the Strength Through Joy programme, which provided leisure activities and cheap holidays as a means of promoting the party's ideology. She ran aground off Thorshavn, Faroe Islands, on 23 July 1934, but was refloated the next day.

At the start of World War II, Monte Rosa was allocated for military use. She was used as a barracks ship at Stettin, then as a troopship for the invasion of Norway in April 1940. She was later used as an accommodation and recreational ship attached to the battleship Tirpitz, stationed in the north of Norway, from where Tirpitz and her flotilla attacked the Allied convoys en route to Russia. In November 1942, she assisted in the deportation of Norwegian Jewish people, carrying a total of 46 people from Norway to Denmark, of whom all but two later died in Auschwitz concentration camp.

At the end of March 1944, Monte Rosa was attacked by Royal Air Force Bristol Beaufighters, of 144 Squadron and 404 Squadron. The attack was mounted for the explicit purpose of sinking her, after British Intelligence had obtained details of the ship's movements. The RAF crews claimed two torpedo hits and eight hits with RP-3 rockets. In June 1944, members of the Norwegian resistance movement attempted, but failed to sink her by attaching Limpet mines to her hull.

Later in 1944, Monte Rosa served in the Baltic Sea, rescuing Germans trapped in Latvia, East Prussia and Danzig by the advance of the Red Army. In May 1945, she was captured by advancing British forces at Kiel and taken as a prize of war.

In 1946, Monte Rosa was assigned to the British Ministry of Transport and converted into a troopship. By this time, she was the only survivor of the five Monte-Class ships. The Monte Cervantes sank near Tierra del Fuego in 1930, one ship was sunk by an air-raid in 1942; one was badly damaged by bombs and scrapped after the war. The Monte Pascoal was scuttled by the British in 1946.

Monte Rosa was renamed HMT Empire Windrush on 21 January 1947, for use on the Southampton-Gibraltar-Suez-Aden-Colombo-Singapore-Hong Kong route, with voyages extended to Kure in Japan after the start of the Korean War. The vessel was operated for the British Government by the New Zealand Shipping Company, and made one voyage only to the Caribbean before resuming normal trooping voyages.

The new name was one of a series of ship names used by the British government for the vessels that were acquired or chartered for the carriage of troops. Many of these ships were second-hand (like Empire Windrush), and were renamed when bought. The names were "Empire" followed by the name of a British river; in this case the River Windrush, a minor tributary of the Thames, flowing from the Cotswold hills towards Oxford.

In May 1949, Empire Windrush was on a voyage from Gibraltar to Port Said when a fire broke out on board. Four ship were put on standby to assist if the ship had to be abandoned. Although the passengers were placed in the lifeboats, they were not launched and the ship was subsequently towed back to Gibraltar.

IMMIGRATION FROM JAMAICA

In 1948, Empire Windrush, which was en route from Australia to England via the Atlantic, docked in Kingston, Jamaica to pick servicemen who were on leave. The British Nationality Act 1948 had just been passed, giving British citizenship to all people living in Commonwealth countries, and full rights of entry and settlement in Britain. The ship was far from full, and so an opportunistic advertisement was placed in a Jamaican newspaper offering cheap transport on the ship for anybody who wanted to come and work in the UK. Many former servicemen took this opportunity to return to Britain with the hopes of rejoining the RAF, while others decided to make the journey just to see what England was like. The resulting group of 492 immigrants famously began a wave of migration from the Caribbean to the UK, and the name Windrush has as a result come to be used as shorthand for that migration, and by extension for the beginning of modern British multicultural society.

The arrival of the ship immediately prompted complaints from some members of parliament, but legislation controlling immigration was not passed until 1962. Among the passengers was Sam Beaver King who went on to become the first black Mayor of Southwark. There were also the calypso musicians Lord Kitchener, Lord Beginner, Lord Woodbine and Mona Baptiste, alongside 60 Polish women displaced during the Second World War. There were several stowaways. One, Averill Wauchope, was a "25-year-old seamstress" who was discovered seven days out of Kingston. A whip-round was organised on board ship, raising £50 – enough for the fare and £4 pocket money for her. Nancy Cunard, heiress to the Cunard shipping fortune, who was on her way back from Trinidad, "took a fancy to her" and "intended looking after her"

The arrivals were temporarily housed in the Clapham South deep shelter in south-west London, less than a mile away from the Coldharbour Lane Employment Exchange in Brixton, where some of the arrivals sought work. Many only intended to stay for a few years, and although a number returned the majority remained to settle permanently.

In 1998, an area of public open space in Brixton, London, was renamed Windrush Square to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the arrival of Windrush's West Indian passengers. To commemorate the "Windrush Generation", in 2008, a Thurrock Heritage plaque was unveiled at the London Cruise Terminal at Tilbury. This chapter in the boat's history was also commemorated, although fleetingly only, in the Pandemonium sequence of the Opening Ceremony of the Games of the XXX Olympia in London, 27 July 2012. A small replica of the ship plastered with newsprint was the facsimile representation in the ceremony.

EVENTS ON HER FINAL VOYAGE

The Emprie Windrush set off from Yokohama, Japan in February 1954 on what proved to be her final voyage. She called at Kure and was to sail to the United Kingdom. Her passengers including recovering wounded United Nations veterans of the Korean War, some soldiers from the Duke of Wellington's Regiment wounded at the Third Battle of the Hook in May 1953, and also military families. However, the voyage was plagued with engine breakdowns and other defects and it took ten weeks to reach Port Said, from where the ship sailed for the last time.

An inquiry later found that an engine room fire began after a fall of soot from the funnel fractured oil-fuel supply pipes. The subsequent explosion and fierce oil-fed fire killed four members of the engine room crew. The fire could not be fought because of a lack of electrical power for the water pumps because the back-up generators were also not in working order and the ship did not have a sprinkler system. The lack of electrical power also prevented many lifeboats from being launched and the remainder were unable to accommodate all the survivors, who were mostly clad in their nightclothes.

Despite these difficulties, the only fatalities were the four crew killed in the engine room – all 1,276 passengers were saved. The rescue vessels took them to Algiers, where they were cared for by the French Red Cross and the French Army. Assistance was given by MV Mentor, MV Socotra, SS Hemsefjell and SS Taigete. A Shackleton from 224 Squadron, Royal Air Force assisted in the rescue

The burned-out hulk of Empire Windrush was taken in tow by the Bay-class anti-aircraft

frigate HMS Enard Bay of the Royal Navy's Mediterranean Fleet, 32 miles northwest

of Cape Caxine. HMS Enard Bay attempted to tow the ship to Gibraltar in worsening

weather, but Empire Windrush sank in the early hours of the following morning,

Monday, 30 March 1954. The wreck lies at a depth of around 2,600 metres (8,500

ft).

OFFICIAL ENQUIRY REPORT

THE MERCHANT SHIPPING ACT, 1894

REPORT OF COURT

(No. 7983)

m.v. "Empire Windrush" O.N.181561

In the matter of a Formal Investigation held at 11-12, Charles II Street, London, on the 21st, 22nd, 23rd, 24th, 25th, 28th, 29th and 30th days of June, and the 1st, 2nd, 5th and 6th days of July, 1954, before Mr. J. V. Naisby, Q.C., assisted by Mr. H. A. Lyndsay, M.I.N.A., Captain H. S. Hewson and Mr. J. R. C. Welch, M.I.Mar.E., F.C.M.S., into the circumstances attending the loss of the motor vessel "Empire Windrush" as the result of fire with the loss of four members of the engine room staff.

The Court having carefully inquired into the circumstances attending the above-mentioned shipping casualty, finds for the reasons stated in the Annex hereto, that it is unable to determine the actual or probable cause of the fire.

Dated this 27th day of July, 1954.

J. V. NAISBY, Judge.

We concur in the above Report,

Â

H. S. HEWSON

J. R. C. WELCH

Assessors

For the reasons stated in the Annex hereto I am of opinion that the most probable cause of the fire was a failure of a portion of the main uptake which released a quantity of burning material into the engine room with the consequent fracture of oil fuel piping due to intense heat.

H. A. LYNDSAY, Assessor

This Inquiry was held at 11-12, Charles II Street, London, on the 21st, 22nd, 23rd, 24th, 25th, 28th, 29th and 30th days of June, and the 1st, 2nd, 5th and 6th days of July, 1954.The "Empire Windrush" was owned by Her Majesty, represented by the Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation, and was managed by New Zealand Shipping Company Limited. The person charged with the duties of her designated manager was Mr. Francis Evelyn Harmer, although his name did not appear on the ship's register as such manager.

The managers, New Zealand Shipping Company Limited, the designated manager, Mr. Harmer, the master of the vessel, Captain Wilson, and her chief engineer, Mr. Christian, were parties to the Inquiry at the beginning thereof. Mr. W. Porges, Q.C., and Mr. Kenneth McGuffie (instructed by the Treasury Solicitor) appeared on behalf of the Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation; Mr. Roland Adams, Q.C., and Mr. S. Knox Cunningham (instructed by Messrs. William A. Crump & Son), appeared on behalf of the Managers, the designated manager, the master, and the chief engineer; Mr. Gerald Darling (instructed by Messrs. Ingledew Brown, Bennison & Garrett), held a Watching Brief on behalf of the Navigators' and Engineer Officers' Union. On the second day of the Inquiry, Mr. S. Silverman, solicitor, appearing on behalf of the relatives of Mr. L. Pendleton, the eighth engineer, applied to be made a party, and the application was granted. At a later stage in the proceedings Mr. Silverman was also instructed on behalf of the relatives of Mr. G. Stockwell, the senior third engineer, and applied to be made a party to the proceedings. This application was also granted.

The "Empire Windrush" was a twin screw motor ship built in 1930 by Blohm & Voss in Hamburg, and came under British ownership and registry in 1947, and was thereafter employed as a troop ship. Her gross tonnage was 14,651; she was 501 feet in length, 65.7 feet in breadth and 37.8 feet in depth. She was built of steel, and had five decks up to and including the uppermost continuous deck, known as "C" Deck, and above that were the promenade deck ("B"), the boat deck ("A"), and the navigating bridge deck. She was divided into eight water-tight compartments extending to "D" Deck, and her machinery space was just about and abaft amidships.

There were four power operated water-tight doors, one separating the boiler room from the engine room, one at the entrance to each of the tunnels and one at the steering flat entrance to the tunnels. The latter was a horizontal door; the other three were vertical. The power operating these doors was of the hydraulic-pneumatic type and employed an accumulator tank filled with air and water situated in the main engine room, the pressure in the tank being four hundred pounds per square inch. Loss of water through leakage was made good automatically by an electrically driven pump. Under normal circumstances these doors could all be closed or opened simultaneously by operating a cock on the bridge. They were also capable of being operated individually from either side. An emergency hand pump and controls situated inside the engine casing at "C" Deck level were provided for use in the event of a complete loss of pressure. On "E" Deck there were eleven water-tight doors of the hand-operated hinged type, with fireproof doors in the same openings. On "D" Deck there were ten fireproof doors; on "C" Deck three; and two each on "A" and "B" Decks. All the fireproof doors except two were of the spring-loaded self-closing type. The fireproof bulkheads were of steel, except in way of cabins and public rooms, where they were composed of granulated slabs of fire-resisting material about two inches thick, reinforced by steel wire mesh, and had wood panelling. There were two tunnel escapes extending from the tunnel to the underside of "C" Deck and giving access to "D" Deck. The after tunnel recess was divided on the centre line by a bulkhead in which there was an opening in which a steel door was fitted. There were 55 electrically-driven supply fans, 24 exhaust fans, and one combined supply and exhaust fan situated on the upper decks, and where the ventilation trunks passed through fireproof bulkheads they were fitted with hinged dampers. Five of these supply fans and two of the exhaust fans were for the engine room and two for the boiler room, and the main ventilation outlet for these two spaces was by the after or working funnel.

The "Empire Windrush" was propelled by four sets of M.A.N. internal combustion engines coupled in pairs to two propeller shafts. Each engine had six cylinders and developed about 2,000 indicated horsepower. The engines had originally been designed for blast injection, but in 1950 were converted to solid injection.

There were three 350 Kw. direct current electric generators driven by internal combustion engines of the trunk piston type arranged along the starboard side of the engine room. An additional generator was installed in 1949 in a specially constructed compartment at the forward end of, and between, the two shaft tunnels, but at the time of the casualty this generator was unserviceable. An emergency generator and switchboard were situated at the after end of "D" Deck. Cooling water for this generator could be provided either by a special cooling pump or from the emergency fire pump. Both of these pumps were situated in the steering flat and were electrically driven.

The following circuits were connected to the emergency switchboard; five for boat winches, five for emergency lighting, and one each for the navigation lights, the wireless, the emergency bilge pump, the emergency fire pump, the emergency generator cooling pump, and the alternative circuit to the steering gear. Between the main switchboard and the emergency switchboard there was an interconnecting main which could be broken by isolating switches of the knife type, one on either board. There was also a wire connecting the circuit breaker on the emergency board to a trip coil for opening the main to emergency circuit breaker on the main switchboard. This was for the purpose of disconnecting the main switchboard from emergency board before the circuit breaker on the emergency switchboard was closed.

The fire appliances included: 94 portable extinguishers distributed throughout the accommodation, 14 portable extinguishers in the machinery spaces, fire pumps in the machinery spaces, and two extinguishers, each of 34 gallons capacity, also in the machinery spaces; the emergency fire pump in the steering gear flat and 58 hydrants distributed throughout the decks and 5 hydrants in the machinery spaces. There were 14 manual fire alarms distributed throughout the vessel; two firemen's outfits, including smoke helmets; smothering steam to the holds; a smoke detection system for the after and forward ends of the ship; smothering steam to the boiler room and a froth installation for the boiler room. All fire appliances were in compliance with the regulations in force at the time of the casualty. The system for smothering steam to the boiler room was capable of being operated from the working alleyway on "E" Deck, and on this occasion was so operated. The controls for the froth installation in the boiler room were situated on the "E" Deck level, just inside the engine room door opening out of the working alleyway.The life-saving appliances throughout were in compliance with the regulations, and included 22 lifeboats, with a capacity of 1,571 persons. Of the lifeboats, 20 were stowed in double tiers, the same davits and falls being used for both upper and lower boats. Recovery of the falls could be effected by hand or power. 20 units of buoyant apparatus, each for 20 persons, were distributed throughout the ship, and there was an inflatable rubber raft for 20 persons stowed on the fore deck; 18 lifebuoys and 1,980 life jackets, including 80 children's jackets, were provided.

Electric alarm bells and a Tannoy loudspeaker system were fitted throughout the vessel, both systems being operated by current from the ship's main. There was an air siren on the fore mast, an air whistle on the front of the forward funnel and a steam whistle on the front of the after funnel all operated electrically by push buttons from the bridge, and the steam whistle could also be operated by a lanyard. The vessel was equipped with a main and emergency wireless transmitter and receiver, and two of the life boats were also fitted with emergency transmitters and receivers.There was a telephone system fitted on board, providing communication between various parts of the vessel, including the bridge, the engine room, and the chief engineer's cabin. The power for the telephone system was supplied from batteries.

There were two cylindrical Scotch type boilers supplying steam for operating some of the auxiliary machinery and fitted for burning oil or for using exhaust gas from the main engines. The remainder of the auxiliary machinery was electrically driven. The daily service tanks for main engines and generators were situated on "F" Deck level immediately forward of the bulkhead dividing the engine room from the boiler room with service pipes from these tanks leading through the bulkhead into the engine room. The lubricating oil and fuel oil gravity tanks were sited on "E" Deck level at the after end of the engine casing. On "E" Deck level, from the working alleyway on the starboard side, there was an entrance closed by a single door to the boiler room, and an entrance closed by a double door to the engine room.

The approximate quantities of oil in these tanks at the time of the casualty seem to have been:Main engines daily use tank, port

25 tons

Main engines daily use tank, starboard

19 tons

Generator daily use tank, port

13 tons

Generator daily use tank, starboard

14 tons

Gravity tank

10 tons

The starboard lubricating storage tank was empty, and the port tank contained about 1,000 gallons.

The exhaust gases from the main engines were led to a common manifold. From this they could be passed either directly up the main uptake or through the boilers for the production of steam. The exhaust from the boilers was also passed up the main uptake, as was the exhaust from the three generators on the starboard side.

On the morning of the 28th March, 1954, the "Empire Windrush" was in the Mediterranean Sea proceeding westwards returning to this country from the Far East in the course of a trooping voyage with 1,276 passengers on board, and manned by a crew of 222 all told. About 0617, when the vessel was about 30 miles to the northward and westward of Cape Caxine, the master and chief officer, who were on the bridge, heard a "whoof" of air and, turning round, saw black smoke which had just commenced to issue from the funnel, followed almost immediately by tongues of flame. An attempt was made to telephone to the engine room, but although it could be heard that the telephone was ringing, no reply was received. The engine room telegraph was at once rung to stop, but the order was not acknowledged from the engine room and the telegraph was returned to the full ahead position. The chief officer at once proceeded to the after deck where a deck squad, mainly comprised of members of the crew previously detailed as a fire fighting party, were known to be washing down the after deck. With this squad he immediately proceeded to the working alleyway on "E" Deck and found that the double door to the engine room was already very hot, and he could see a bright orange flame round the sides of the doors and through the division between the doors. Hoses were at once put into operation and at first there was water in the hoses, but within a matter of minutes the supply of water failed. Meanwhile, the chief officer had sent various members of his party to other decks to bring hoses to bear on the outside of the engine room casing in order to prevent the spread of the fire, and he then returned to the bridge to report to the master.

The chief engineer had also been called by the telephone to his cabin and informed that there was something wrong in the engine room, and he immediately went to the engine room, sending a steward to call the second engineer on his way. The chief and second engineers proceeded to the working alleyway where the hose party was already in operation, found that it was impossible to enter the engine room by the double doors, looked into the boiler room entrance which also opened out of the working alleyway and found that, although there was no flame in the boiler room, the smoke was so thick that they were driven out after they had gone one or two steps down the ladder. They then went to the engine room by way of the port tunnel, and the Chief Engineer was able to get a few feet inside the entrance. At that time he saw no sign of fire, but there was very dense black smoke and he was unable to breathe. A smoke helmet was sent for, and the second engineer put it on and went into the engine room, but owing to the thickness of the smoke could see nothing except that when he got a few feet inside the engine room, level with the lubricating oil pumps there was a floor plate missing, and at that time he saw a glow of fire through the smoke between the two inner main engines, the centre of the glow being about midway between the centre grating and the bottom plates. An attempt was made to close the door leading from the engine room to the port tunnel, but there was no power. The second engineer tried to telephone the bridge from the steering flat, but the telephone was out of action. The chief engineer went to the bridge to report to the master. The remote controls for the supply of oil from the daily use tanks which were situated in the working alleyway were operated under the orders of the second engineer in order to shut off the supply of fuel oil for the main engines and generators. The steam smothering supply for the boiler room was also turned on.

At the time that the " whoof" of air was heard by the master and chief officer, there were three engineers, an electrician and a greaser in the engine room, and a greaser in the boiler room. The man in the boiler room was at the forward end of the space on the port side when he saw a flash "coming from the inboard side of the starboard boiler - a flash, as of fire; a reddish glow". There now seems no doubt that this light was a reflection from the side of the starboard boiler. He went between the boilers, where the door leading from the boiler room to the engine room was straight in front of him, and saw that there was a glow coming from the engine room. He stepped just through the water-tight door into the engine room, and what he described as a wall of flame "just seemed to fall down" in front of him. He then stepped back into the boiler room, turned round and heard a "whoof," and immediately the lights went out. He then proceeded to leave the boiler room by way of the door into the working alleyway and, having got part way, turned back to light an improvised torch at one of the boilers, then climbed up to the "E" Deck level and went through the door into the working alleyway where the hose party already were.

The greaser in the engine room was at the after end of the engine room on the port side when he saw a sheet of flame coming from between the inner main engines. He then went into the port tunnel, heard what he described as a kind of " whoof"; the lights in the engine room went out, but he stated that those in No. 4 generator room were still on. He waited in the port tunnel for some little time, and then began to make his way aft along the tunnel in the darkness when he met the chief and second engineers coming down with a torch and returned with them to the tunnel door.

The three engineers and the electrician in the engine room were probably all together in the engineers' store, and the Court has very little doubt that they were almost immediately trapped by the fire.

To return to what was happening on the bridge, it is impossible to be certain of the chronology or sequence of events. Naturally enough, no one was taking times, and the recollections of the various witnesses are not altogether in agreement as to the exact sequence of events. Very shortly after the chief officer left the bridge, however, to go and direct the fire fighting operations, an attempt was made to close the water-tight doors in the machinery space by means of the master control on the bridge. This failed. An attempt to pass orders over the Tannoy system also proved that there was no power on that system. An attempt to operate the electric alarm bells also failed. The air siren on the foremast and the air whistle on the forward funnel were also out of action, and the steam whistle emitted water on being tried. It was also found that the vessel was ceasing to steer. About 0620 the master gave the fourth officer, who was the junior officer of the Watch, orders to call the wireless operator on to the bridge, work out the ship's position and give it to the wireless operator, and an S.O.S. message was sent out, probably at 0623, and repeated thereafter. About the same time orders were given for emergency stations. These orders were passed by word of mouth. The fire continued to spread with great rapidity, and probably about 0645 orders were given to embark the passengers in the lifeboats. The first tier of lifeboats took off some two-thirds of the total number on board, including all the women and children. The falls from these lifeboats were being recovered in order to lower the second tier but as there was no power on the winches to recover the falls, this proved to be a slow process. In view of the rapidity of the spread of the fire, orders were given to tumble the remaining lifeboats overboard. This was done by the crew with some help from the naval and military personnel on board, all rafts and buoyant apparatus and anything that would float were thrown overboard, and the remainder of the passengers and crew scrambled down rope ladders, slid down ropes or fire hoses which were thrown over the side or, in some few cases, jumped. Many of them got into the boats, but some of them went into the water and they were all picked up by the lifeboats of the "Empire Windrush", with the exception of a few who were picked up by a lifeboat from the "Socotra". In response to the wireless messages from the "Empire Windrush", four vessels which were in the vicinity, the "Socotra", the "Mentor", the "Hemsefjell", and the "Taigete", had speedily arrived upon the scene and between them they took on board the whole of the passengers and crew from the "Empire Windrush" and landed them at Algiers.

There is no doubt that the failure of power and light on the "Empire Windrush" was due to the fire in the engine room. At a very early stage, attempts were made to put the emergency generator into action. The generator itself was started without any trouble, but it proved impossible to get the power from the generator transferred to the switchboard because the main circuit breaker would not stay in. The Court is satisfied that there is more than one way in which the failure to get the main circuit breaker on the emergency switchboard to stay in could have been, and very probably was, caused by the fire.

In the alarming emergency which arose, the conduct of both passengers and crew on board the "Empire Windrush" is beyond all praise. Despite the failure of the aids which would normally be expected to be available in controlling the embarkation of such numbers, the abandonment of the vessel proceeded smoothly. In the words of one witness, everybody on the ship seemed to be doing exactly the right thing. Perhaps no higher tribute can be paid to the organisation both by the ship's company and the military officers on board, or to the discipline, coolness and courage of the passengers. The Court also desires to acknowledge with gratitude the assistance given by the masters and crews of the four vessels mentioned, the "Socotra", "Mentor", "Hemsefjell", and the "Taigete", and also to express its appreciation of the courtesy and efficiency of the French authorities in Algiers under the direction of the Commanding General of that District.

About 0945 on the 28th March, the Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean ordered two destroyers from Gibraltar to proceed to the assistance of the "Empire Windrush", but before they got to her it was known that the passengers and crew of the "Empire Windrush" had been taken to Algiers. One destroyer accordingly went direct to Algiers, and the other proceeded to the "Empire Windrush" and found the vessel still burning fiercely. About 0945 on the 29th March, H.M.S. "Saintes" arrived at the "Empire Windrush", was able to put a boarding party on board and take the vessel in tow, although the boarding party were not able to remain on board for any considerable length of time. The towage started about 1230 on a course for Gibraltar at a speed of about 3 1/2 knots, but at 0030 on the 30th March, the "Empire Windrush" sank stern first in a position about Lat. 37° N., Long. 02° 11' E.

The "Empire Windrush" was by no means a new ship, and there was considerable criticism of her engines and auxiliary machinery, but the Court sees no reason to doubt that the "Empire Windrush" was, as far as could be ascertained, fit to proceed to, and be at, sea. Whilst employed as a troop ship the "Empire Windrush" has been surveyed by Surveyors of the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation on several occasions and had received a Passenger and Safety Certificate for numbers in excess of those carried on the voyage in question. In several respects the "Empire Windrush" did not comply with the standards laid down in the Merchant Shipping (Construction) Rules, 1952. With one small exception, however, she did comply with the Merchant Shipping (Life-Saving Appliance) Rules, 1952, and she did comply with the Merchant Shipping (Fire Appliance) Rules, 1952. The 1952 Rules were made by the Minister of Transport under powers conferred upon him by the Merchant Shipping (Safety Convention) Act, 1949, which was passed for the purpose of putting into effect the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1948. The date on which these Rules came into force was fixed by the Convention itself and was the 19th November, 1952. Many of the requirements of the Convention with regard to construction, whilst possible to incorporate in the building of a new ship, were impracticable of application to an existing ship, and this fact was recognised in the Convention itself, which provided in Chapter II Regulation l(a)(i): "Unless expressly provided otherwise, this Chapter applies to new ships. (ii) In the case of existing passenger ships ... which do not already comply with the provisions of this Chapter relating to new ships, the arrangements on each ship shall be considered by the Administration, with a view to improvements being made to provide increased safety where practicable and reasonable". Even before the 1952 Rules came into force, a considerable amount of work had been done on the "Empire Windrush" to make the vessel comply with the 1952 Rules where practicable and to conform as nearly as possible thereto where it was impracticable to comply with the strict wording of the Rules.

On behalf of the relatives of two of the engineers who lost their lives in the fire, it was contended that the vessel was unlawfully at sea in that she was not provided with the appropriate certificate or certificates under the Merchant Shipping (Safety Convention) Act, 1949, and that the vessel did not comply with the 1952 Rules and had not been validly exempted from compliance with any of them. These submissions raise a difficult point of law on the construction of the Merchant Shipping (Safety Convention) Act, 1949, and the 1952 Rules made thereunder. In the opinion of the Court, it is not necessary for the purposes of this Inquiry to decide this point of law, as the Court is satisfied that whether or not the permission given to the "Empire Windrush" to proceed to sea was in the proper form, namely, even if the Passenger and Safety Certificate actually given was invalid, she was nonetheless in such a condition that a valid certificate could properly have been given under the Act and the Rules, and that, in these circumstances, whether the certification was valid or not has no bearing on the cause of the loss.

It is clear that within a very short time there was at the forward end of the engine room on the starboard side a fire of great intensity and there is no doubt that the intensity of the fire and the rapidity with which it spread was due to the fact that it was oil fed. This fire within a few minutes affected the electric lighting, communication and power systems and the hydraulic-pneumatic system for closing the watertight doors in the engine room as well as the main and auxiliary machinery, thus reducing and almost eliminating the chances of fighting or confining the fire.

From the point of view of confining and fighting fire, the immediate closing of all water-tight and fireproof doors is an obvious precaution which is not always taken. Other considerations however have to be borne in mind and the Court does not think that Captain Wilson was to blame for not ordering the closing of such doors as soon as he was aware that there was something wrong in the engine room. Such action on his part might have deprived those in the machinery space of their chance of escape and might have tended to create alarm amongst the passengers. Although no general order to close either water-tight or fireproof doors was given, attempts were made to close the water-tight doors at a comparatively early stage. The ship's standing orders for Emergency and Fire Stations provided for some member of the crew to stand by each fireproof door and convention valve and there was evidence to show that many of these were closed. It is probable that others which were not spoken to by such of the witnesses as gave evidence at the Inquiry were also closed.

Various possible causes of the fire were considered. In the opinion of the Court it is improbable that the origin of the fire was due to a crank-case explosion either in the main engines or the generators. Smoking, electrical fault, and sabotage are also considered improbable.

Two more probable causes are:(1) The collapse of a plate in the main uptake causing incandescent material at a high temperature to be deposited at the forward end of the engine room probably towards the starboard side. Most of this material would probably fall on the platform just inside the entrance to the engine room at "E" Deck level. This platform was of chequered plate with two openings on the centre line but the forward end was a grating under which fuel and lubricating oil pipes were led in a thwartship direction. Such material on exposure to the air would burst into flame and either by physical contact or by heat cause a pipe to give way, and vapourise and ignite the oil therefrom. There was no evidence given at the Inquiry as to whether the upper part of the main uptake had ever been renewed or repaired since the vessel was built and it did not seem that there was any requirement that the uptake should be inspected internally or that there was any practice to make such an examination. The uptake was lagged so external examination of the plate which must have been liable to corrosion was impossible.

(2) The spraying, dripping or splashing of oil, probably fuel oil, on to a hot exhaust "Y" piece, or pipe. There were a number of fuel supply lines of various diameters passing above or adjacent to the main engines. In order to get the fuel to the engines it is inevitable that at least a certain number of these supply lines must be in some such position. If one of these pipes fractured or became adrift it would have been possible for oil therefrom to spray, drip or splash in comparatively small quantities on to a hot exhaust "Y" piece or possibly some part of the exhaust pipe where the lagging of that pipe was not perfect. According to the evidence in such event that oil would vaporise and might ignite. Had that happened such ignition might well provide a sufficient "match" to set alight to the main flow of oil from the pipe and create almost instantaneously a fire of the intensity spoken to in evidence and also produce a large quantity of dense acrid smoke.

Having carefully considered the above causes of the origin of the fire I have come to the conclusion that on the evidence given there is no such balance of probability in favour of any one as to justify me in finding that it was the probable cause of this fire.

The Court recommends that consideration should be given:(1) To an alteration in the requirements for firefighting appliances by a considerable increase in the number of smoke helmets provided and to their distribution.

(2) To the question of making it imperative that there should be a proper periodical examination and inspection of uptakes and funnels in all vessels.

(3) To the question of the dispersal of emergency controls and connections.

J. V. NAISBY, Judge.

We concur in the above Annex to the Report,

Â

H. S. HEWSON

J. R. C. WELCH

Assessors

I also concur except as to the two paragraphs above preceding the Court's recommendations. I have carefully considered all the evidence given in Court and consider that by far the most probable cause of the fire on the "Empire Windrush" was a failure of a portion of the combined uptake from the main engines, main generators and composite boilers, which thereby released a quantity of burning material into the engine room and the consequent fracture of oil fuel piping due to intense heat.

The principal reasons leading to this conclusion may be summarised as follows:It is not known whether the uptake had been renewed since the ship was built but in any event, even if it had been renewed, there is no record of the inside of the funnel above the level of the top of the economisers having even been seen since 1947. To reduce heat radiation the exterior of the uptake was completely covered with asbestos mats which were held in place in the usual manner by steel bands fitted over the mats with the uptake itself being used as the necessary support. The uptake was constructed of steel plate and due to the purpose for which it is intended it is not practicable permanently to protect its internal surface against the corrosive effects of the exhaust from internal combustion engines or the gas from oil-fired boilers. As the uptake is open at the top there would be no tendency for hot gases to leak through a defective uptake sheathed with mats to give any indication of its condition and in any case the uptake would be gas tight if its steel plates were even of paper thickness. Should, however, the uptake become so corroded as to be unable to support the weight of the insulation mats then one or more of these would become detached. The inside of the uptake from an oil-fired boiler has normally a quantity of soot and other semi-burnt material adhering to its inner surface and without support this will fall and during its passage through the air some of this material if not already alight will burst into flame. In this case, this would give the effect of a flash or glow high up in the engine room from which position there is evidence that the fire was first observed.

The characteristic "whoof" of the domestic chimney fire was also noted while there were several clear statements as to the absence of an explosion.

In this connection, several witnesses described an "acrid" smoke which became evident almost immediately and was variously described as "likeinsulation", "like an electrical blow-out" or "something like a burning chimney".

The most vulnerable position in the funnel on the "Empire Windrush" was the sloping plate at the elbow about 50 feet above the highest point inspected by sight only. This plate was directly over the platform at the entrance to the engine room at "E" Deck and the bulk of any material falling from this position would be deposited on the platform. The platform just inside the door is of chequered plate with two openings on the middle line directly over No. 1 and 2 cylinders of the inboard pair of main engines. The platform extended right across the casing at this level but it is understood that at the fore end there was an open grating under which fuel oil pipes passed. If incandescent material did fall from the funnel some would lodge on the platform just inside the double door on "E" Deck, some would pass through the openings to land on the engine floor plates just between the engines and some might be expected to land on the oil fuel pipes just below the grating. It has been given in evidence that within a very short space of time from the first indication of an accident, there was an intense fire near the door into the engine room at "E" Deck level and a glow low down between the engines.

To ignite oil fuel in quantity a large source of heat is necessary and in my opinion a glowing mass of incandescent soot would supply the necessary match and the continued supply of oil could readily be obtained from the pipes under the grating.The gradual failure of the main engines and generators was most probably due to the depletion in the engine room of oxygen and evidence was given that the greaser noted a rush of air and black smoke coming up the tunnel from the engine room shortly after he heard the " whoof." The fact that probably the fuel system was damaged would be a secondary contributory factor.

The accident occurred with extreme suddenness and the fact that there were no survivors would also support the theory that burning material fell without warning and, not only absorbed all the available oxygen in the engine room, but also released large quantities of noxious gases.

H. A. LYNDSAY, Assessor

11947 Wt.3134/3187 K9 9/54